R Setup

Last updated on 2025-12-23 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What is R, what is R Studio?

- How to work with the R console and R scripts?

- What is an R package?

Objectives

- To gain familiarity with the various panes in the RStudio IDE

- To gain familiarity with the buttons, short cuts and options in the RStudio IDE

- To understand variables and how to assign to them

- To be able to manage your workspace in an interactive R session

- To be able to use mathematical and comparison operations

- To be able to call functions

- Introduction to package management

Introduction to RStudio

Welcome to the R portion of the Empra. This first lesson is adapted from resbaz’s introction to R workshop.

Throughout this lesson, you’re going to learn some of the fundamentals of the R language as well as some best practices for organizing code for scientific projects that will make your life easier.

We’ll be using RStudio: a free, open source R integrated development environment. It provides a built in editor, works on all platforms (including on servers) and provides many advantages such as integration with version control and project management.

Basic layout

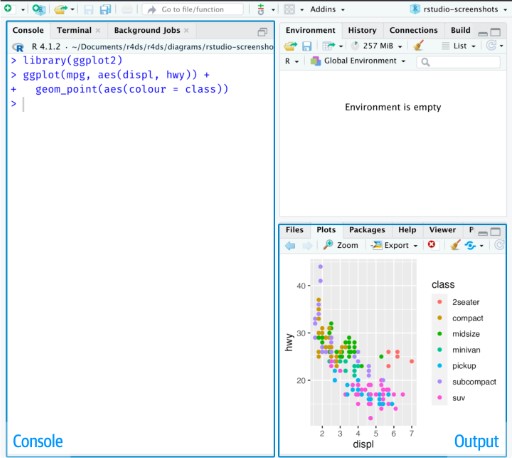

When you first open RStudio, you will be greeted by three panels:

- The interactive R console (entire left)

- Environment/History (tabbed in upper right)

- Files/Plots/Packages/Help/Viewer (tabbed in lower right)

Once you open files, such as R scripts, an editor panel will also open in the top left.

Work flow within RStudio

There are two main ways one can work within RStudio.

- Test and play within the interactive R console then copy code into a

.R file to run later.

- This works well when doing small tests and initially starting off.

- It quickly becomes laborious

- Start writing in an .R file - called a script - and use RStudio’s

command / short cut to push current line, selected lines or modified

lines to the interactive R console.

- This is a great way to start; all your code is saved for later

- You will be able to run the file you create from within RStudio or

using R’s

source()function.

For now, let’s stick with the console. We will learn more about how to use R scripts later. Feel free to run all code examples provided here in your own RStudio console and figure out what they do.

Introduction to the R console

Much of your time in R will be spent in the R interactive console. This is where you will run all of your code, and can be a useful environment to try out ideas before adding them to an R script file.

The first thing you will see in the R interactive session is a bunch of information, followed by a “>” and a blinking cursor. R operates on the idea of a “Read, evaluate, print loop”: you type in commands, R tries to execute them, and then returns a result.

Using R as a calculator

The simplest thing you could do with R is do arithmetic:

R

1 + 100

OUTPUT

[1] 101And R will print out the answer, with a preceding “[1]”. Don’t worry about this for now, we’ll explain that later. For now think of it as indicating output.

If you type in an incomplete command, R will wait for you to complete it:

OUTPUT

+Any time you hit return and the R session shows a “+” instead of a “>”, it means it’s waiting for you to complete the command. If you want to cancel a command you can simply hit “Esc” and RStudio will give you back the “>” prompt.

Tip: Cancelling commands

If you’re using R from the commandline instead of from within

RStudio, you need to use Ctrl+C instead of Esc

to cancel the command. This applies to Mac users as well!

Cancelling a command isn’t just useful for killing incomplete commands: you can also use it to tell R to stop running code (for example if its taking much longer than you expect), or to get rid of the code you’re currently writing.

When using R as a calculator, the order of operations is the same as you would have learnt back in school.

From highest to lowest precedence:

- Parentheses:

(,) - Exponents:

^or** - Divide:

/ - Multiply:

* - Add:

+ - Subtract:

-

R

3 + 5 * 2

OUTPUT

[1] 13Use parentheses to group operations in order to force the order of evaluation if it differs from the default, or to make clear what you intend.

R

(3 + 5) * 2

OUTPUT

[1] 16This can get unwieldy when not needed, but clarifies your intentions. Remember that others may later read your code.

R

(3 + (5 * (2 ^ 2))) # hard to read

3 + 5 * 2 ^ 2 # clear, if you remember the rules

3 + 5 * (2 ^ 2) # if you forget some rules, this might help

The text after each line of code is called a “comment”. Anything that

follows after the hash (or octothorpe) symbol # is ignored

by R when it executes code.

Really small or large numbers get a scientific notation:

R

2/10000

OUTPUT

[1] 2e-04Which is shorthand for “multiplied by 10^XX”. So

2e-4 is shorthand for 2 * 10^(-4).

You can write numbers in scientific notation too:

R

5e3 # Note the lack of minus here

OUTPUT

[1] 5000Mathematical functions

R has many built in mathematical functions. To call a function, we simply type its name, followed by open and closing parentheses. Anything we type inside the parentheses is called the function’s arguments:

R

sin(1) # trigonometry functions

OUTPUT

[1] 0.841471R

log(1) # natural logarithm

OUTPUT

[1] 0R

log10(10) # base-10 logarithm

OUTPUT

[1] 1R

exp(0.5) # e^(1/2)

OUTPUT

[1] 1.648721Don’t worry about trying to remember every function in R. You can simply look them up on Google, or if you can remember the start of the function’s name, use the tab completion in RStudio.

This is one advantage that RStudio has over R on its own, it has autocompletion abilities that allow you to more easily look up functions, their arguments, and the values that they take.

Typing a ? before the name of a command will open the

help page for that command. As well as providing a detailed description

of the command and how it works, scrolling to the bottom of the help

page will usually show a collection of code examples which illustrate

command usage. Try reading the description to the log()

function by typing ?log() (or just ?log) in

the console.

Comparing things

Another useful feature of R next to functions are comparisons. Quite often, we want to see if one value is bigger than another or only use data with some particular value.

We can check if two values are equal by using the equality operator

==.

R

1 == 1 # equality (note two equals signs, read as "is equal to")

OUTPUT

[1] TRUER

1 != 2 # inequality (read as "is not equal to")

OUTPUT

[1] TRUER

1 < 0 # less than

OUTPUT

[1] FALSER

1 <= 1 # less than or equal to

OUTPUT

[1] TRUER

1 > 1 # greater than

OUTPUT

[1] FALSER

1 >= 1 # greater than or equal to

OUTPUT

[1] TRUEVariables and assignment

In the previous example, we simply used numbers to do comparisons.

However, most work in R will be done using variables. A

variable can be any quality, quantity or property we might be interested

in, like a response time, a score on a personality test or a diagnosis.

We can store values in variables using the assignment operator

<-, like this:

R

x <- 1/40

Notice that assignment does not print a value. Instead, we stored it

for later in something called a variable.

x now contains the value

0.025:

R

x

OUTPUT

[1] 0.025Look for the Environment tab in one of the panes of

RStudio, and you will see that x and its value have

appeared. Our variable x can be used in place of a number

in any calculation that expects a number:

R

log(x)

OUTPUT

[1] -3.688879Notice also that variables can be reassigned:

R

x <- 100

x used to contain the value 0.025 and and now it has the

value 100.

We can also update the value of a variable and store it with the same name again.

R

x <- x + 1 #notice how RStudio updates its description of x on the top right tab

The right hand side of the assignment can be any valid R expression.

The right hand side is fully evaluated before the assignment

occurs. This means that in the above example, x + 1 is

evaluated first and the result is only then assigned to the new

x.

Variable names can contain letters, numbers, underscores and periods. They cannot start with a number nor contain spaces at all. Different people use different conventions for long variable names, these include

- periods.between.words

- underscores_between_words

- camelCaseToSeparateWords

What you use is up to you, but be consistent.

R

this_is_okay

this.is.also.okay

someUseCamelCase

dont_be.aMenace_toSociety

I always use snake_case for variable names in R.

camelCase is often used in other programming languages such

as MATLAB or JavaScript.

Using = for assignment

It is also possible to use the = operator for

assignment:

R

x = 1/40

But this is much less common among R users. The most important thing

is to be consistent with the operator you use. There

are occasionally places where it is less confusing to use

<- than =, and it is the most common symbol

used in the community. So the recommendation is to use

<-.

If we try to give a variable an invalid name, R will throw an error.

ERROR

Error in parse(text = input): <text>:1:2: unexpected input

1: 2_

^Tip: Warnings vs. Errors

Pay attention when R does something unexpected! Errors, like above, are thrown when R cannot proceed with a calculation. Warnings on the other hand usually mean that the function has run, but it probably hasn’t worked as expected.

In both cases, the message that R prints out usually give you clues how to fix a problem.

Errors can be frustrating, but they are your friend! They tell you that something went wrong and usually give you an informative message as to what went wrong. If you cannot make something of the error message, try pasting it into Google or Chat-GPT, this will often help.

Challenges

Challenge 2

What will be the value of each variable after each statement in the following program? You are encouraged to run these commands in R.

R

mass <- 47.5

age <- 122

mass <- mass * 2.3

age <- age - 20

Challenge 3

Run the code from the previous challenge, and write a command to compare mass to age. Is mass larger than age?

- R Studio is a shiny environment that helps you write R code

- You can either write code directly in the console, or use script to organize and save your code

- You can assign variables using

<- - Be consistent in naming variables, other people should be able to read and understand your code